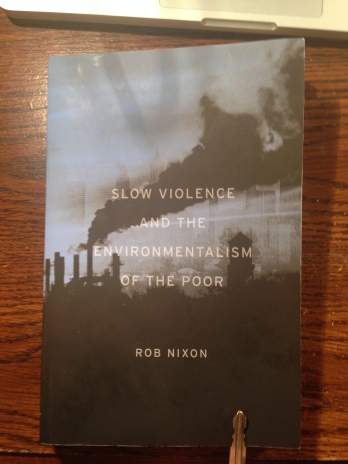

Rob Nixon’s Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor tackles the clash between exploiters of natural resources, driven by desires for short term profit gains, and those native to the exploited areas with no choice but to live with the ecological aftermath. Nixon asserts his theory of slow violence played out in the environmental calamities of the neoliberal age, where technologically developed nations take advantage of material and natural resources in less-developed nations for their own gain, systematically creating a pattern of devastation and abandonment. Slow violence oftentimes occurs out of sight, transparently, dispersed over time and space, and is typically not viewed as violence at all (2). In the face of systematic, structural violence against under protected natural resources in developing countries, Nixon challenges the contemporary ecological criticism movement to “engage representational, narrative and strategic challenges” posed by the hegemonies crafted by systems of slow violence, an effort to combat the lack of excitement and spectacle he asserts important media events inspiring real change require, what he calls “contemporary politics of speed” (2,11).

Nixon begins his survey of the repercussions from ruinous industrial practices in India, exploring the transfer of toxic risk from western corporations to the still-developing nation, one result of which is a toxic gas cloud fictionally rendered in Sinha’s Animal’s People. Having slashed their safety budget, Union Carbide unleashes an accidental (but avoidable) gas cloud that ravages unsuspecting and unprotected natives, a disaster that kills many instantly and affects successive generations who live on contaminated land, eat contaminated food and drink contaminated water. Ideas of corporate transnational distance, foreign bodies and structural neglect demonstrate how free-market ideologies often invite “biological assault” that unevenly disparages the poor (65). He moves on to explore “resource curses,” a phenomenon in which decolonized nations develop into single-resource economies (oil, gas, tourism, coal, etc.) Played out over the last century in the Middle East, Nigeria and Kenya, resource curses have helped institutionalize racism, class warfare, unbridled environmental destruction and oppressive, self-serving oligarchical political regimes. The human cost of fossil fuel industries is asserted as a symptom of slow violence that is rarely visible to the untrained eye; the militarization of economic commerce further degrades natural environments. Nixon expounds upon the symbolic act of tree planting in Kenya, lacing together environmentalism with gender empowerment, democratic community cohesion and steady, non-violent political protest.

The closing chapters of Slow Violence detail the convergences of race, class and ecological impact in spheres of the megadam, game reserve and ecological aftermath of modern, technologically precise warfare (precision to the point of being imprecise). Nixon notes how both mainstream and academic writers in the United States were, on the whole, were failing to notice and publicize the struggle for environmental action around the world, specifically in poorer nations afflicted by slow violence (236). What interested me particularly in Nixon was the failings of corporate responsibility—such as narrative tooling for propaganda purposes and the Corexit dumped in the Gulf of Mexico by BP after their disastrous oil spill (100, 140, 273).

Gonna read it. The caption sounds powerful

LikeLike